The machines are not coming for our jobs in the future; they are already here. The question is not whether AI will transform Ghana’s workforce, but whether we are ready to shape that transformation.

Artificial Intelligence has moved from science fiction to workplace reality. It is embedded in our daily tools, reshaping how we work, learn, and create value. But as AI becomes infrastructural, Ghana faces a critical choice: Will we lead this transformation or let it happen to us?

Recent research from the Institute for AI Policy and Governance reveals both the anxiety and opportunity embedded in Ghana’s AI future. Targeting the rising generation of future professionals, including lawyers, policymakers, educators, and entrepreneurs, the study aimed to capture how these future leaders perceive the impact of AI on jobs, education, and the economy. What emerged reveals both anxiety and opportunity. It’s the reality of a generation caught between fear and possibility that demands immediate policy attention.

The Anxiety is Real, But So is the Opportunity

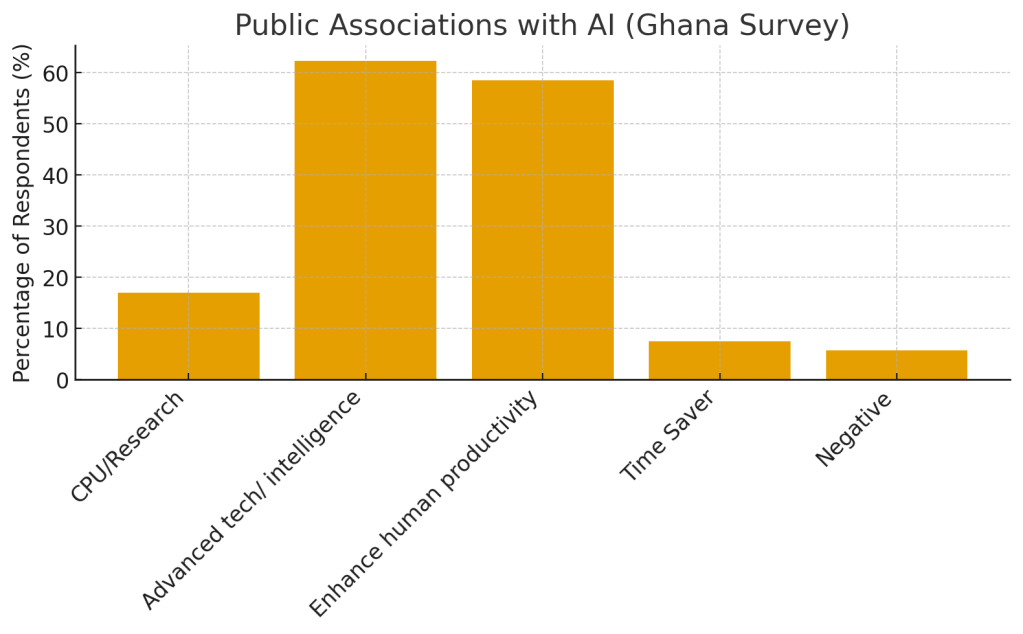

When asked what comes to mind when they hear ‘AI,’ nearly half of respondents described it in terms of advanced or intelligent technology, while about one in three linked it to improved efficiency or productivity. A smaller but notable share (around 10–15%) expressed concerns, using terms like ‘job loss,’ ‘control,’ or ‘dangerous’, reflecting ambivalence about AI’s rapid evolution.

When asked about AI’s impact on Ghana’s job market over the next decade, respondents painted an unsettling picture. The majority (81%) believe AI will significantly reduce job availability, particularly in routine administrative and entry-level analytical roles. This concern is not abstract; it is grounded in the reality of Ghana’s already stretched job market, where youth unemployment and underemployment challenge economic resilience. What is striking, though, is that despite these concerns, 85% of respondents still expressed strong interest in AI-focused training programs. This is not resignation, it is readiness. Ghana’s future workforce recognizes that adaptation is not just beneficial; it is essential.

The “ChatGPT Ceiling” Problem

The data also revealed a fascinating paradox that has significant implications for Ghana’s AI readiness. Let’s break down the key insights:

92% of survey participants are familiar with ChatGPT, vs. 1% being aware of AI in hiring decision making, agriculture (3%), security and surveillance (7%). This reveals a significant awareness gap: while most people recognize AI as a consumer technology, they remain unaware of its institutional applications that directly impact their professional lives, including hiring algorithms, performance monitoring systems, and automated decision-making processes that shape career opportunities and advancement. This is concerning because people can’t advocate against biased AI hiring if they don’t know it exists. AI is reshaping hiring behind the scenes while workers focus on obvious applications. Due to this lack of awareness, job seekers aren’t tailoring their applications for AI screening systems, creating an uneven playing field where some candidates inadvertently learn to optimize for these algorithms while others remain disadvantaged.

Situations like this create policy blind spots: How can we regulate what the public doesn’t understand exists? However, it also presents significant opportunities. Ghana can lead by clarifying AI’s institutional uses before problems arise. Training workers to understand AI hiring systems could give Ghanaian talent a competitive advantage globally. Ghana can build on existing ChatGPT familiarity as a foundation for broader AI literacy and begin immediate education about “invisible AI” in hiring, lending, healthcare, and other sectors. The 92%/1% split is not just a knowledge gap; it is a preview of how AI adoption might create new forms of inequality if we don’t act intentionally. We have a brief window to turn this awareness gap into a competitive advantage through proactive education and transparent governance.

The Skills Gap: A Crisis Hidden in Plain Sight

The data also reveals a troubling disconnect; while respondents identify skills development as AI’s primary workplace impact, nearly half feel inadequately prepared by their current education to work alongside AI. This did not come across as an isolated issue. It is a systemic failure that threatens Ghana’s competitive position in the global economy. One respondent captured this perfectly: “It’s not just about losing jobs. It’s about losing time, time we’ve spent studying for roles that may no longer exist.”

The New Job Geography: Who Thrives, Who Survives

As AI redraws the global job map, it is not just replacing work; it is reshaping who flourishes, who adapts, and who gets left behind. It is selective, strategic, and sometimes surprising, and the next wave of winners and losers depends on how much a role relies on tasks that only humans can still do well:

High-risk roles are often screen-bound: database administrators, IT support specialists, and data engineers, once considered automation-proof, now face significant displacement.

Resilient roles remain hands-on and human-centered: plumbers, caregivers, therapists, and skilled trades continue to resist automation due to their manual, social, or dexterity demands.

Strategic roles leverage uniquely human capabilities: creativity, ethics, complex decision-making, and emotional intelligence become premium skills in an AI-augmented economy.

While this new job map shows who might win or lose, there’s a bigger risk: well-meaning interventions from the Global North often introduce imported solutions that too often overlook local realities, priorities, and the need for homegrown pathways.

The Paternalistic Assumption Problem

Interestingly, very few respondents spontaneously mentioned everyday applications such as AI in agriculture (for crop disease detection or yield prediction) or elections (for misinformation monitoring and data management). This suggests that while awareness of AI as ‘intelligence’ is rising, understanding of its contextual relevance in Ghana’s public sector remains limited. Most respondents (54%) indicated that education will be the sector most transformed by AI, while only 1.5% see healthcare as its biggest frontier, a striking contrast to the dominant narrative and funding focus from external partners, who often position healthcare as AI’s most valuable application in Africa. This observation reveals a profound disconnect between external development agendas and local priorities. The sharp 54% –1.5% split stands in clear contrast to how Global North funders, researchers, and policy advisers typically frame Africa’s “AI future”. This divergence exposes what we might call the “paternalistic assumption problem”, the tendency of Global North actors, often well-meaning, to decide what AI should solve for African countries, without meaningfully engaging those who live and work within local contexts. Ghana’s survey data suggests a fundamentally different understanding of AI’s most transformative potential, one that prioritizes local capacity building.

What Ghana’s Response Reveals

An education-first mindset (54%) shows that Ghanaians recognize that:

- Education is the foundation for all other AI applications.

- Without digital literacy, healthcare AI risks becoming another ineffective imposed solution.

- Educational transformation enables local agency over AI development and develops the skills to shape, adapt, and govern AI tools for Ghanaian realities.

Healthcare skepticism (7%) likely reflects:

- A lived awareness that many healthcare tech pilots fail when they don’t fit local systems.

- A preference for human-centered healthcare solutions over purely technological fixes.

- A clear belief that an educated, digitally literate population must come before healthcare AI can work well.

What is Really Missing? Local Decision Making

Yes, it is absolutely fair to conclude that Global South voices have been largely absent from shaping AI development priorities that directly affect them. If the world wants AI to unlock real value for Ghana, it must move beyond assumptions and invest in listening, co-creating, and empowering the people who know exactly what they need.

The Complement Effect: Why Human-AI Partnerships Win

Emerging research reveals a powerful trend: the complement effect is outweighing the substitute effect. Roles that fuse human and AI capabilities, digital fluency, ethical oversight, collaboration, and team leadership are growing faster and paying better than traditional positions. This is not about humans versus machines. It is about humans with machines creating unprecedented value. Ghanaian workers who can guide, fine-tune, and supervise AI tools won’t just survive; they will define the future of work.

Ghana’s Optimism: A Foundation for Action

Despite legitimate concerns, optimism remains high. The majority of respondents feel confident about finding meaningful employment in the next 5-10 years. This confidence isn’t naive; it is based on a realistic assessment of AI as a tool that can be learned, managed, and directed. Infact the data shows Ghanaians (92%) are already engaging with AI tools, primarily for research, content creation, and learning. This early adoption creates a foundation for more sophisticated human-AI collaboration.

The Policy Imperative: Three Critical Actions

The survey data points to three urgent policy interventions:

1. Emergency Education Reform: Ghana’s educational institutions must immediately integrate AI literacy into curricula. The focus should be on developing the critical thinking, creativity, and ethical reasoning that make humans irreplaceable partners to AI systems, rather than simply teaching students to use ChatGPT.

2. National Reskilling Initiative At the national level, we must launch a comprehensive reskilling program targeting workers in high-risk sectors to focus on developing AI-adjacent skills: prompt engineering, data fluency, oversight roles, and human-AI interface design.

3. Innovation Ecosystem Development Ghana needs policies that encourage local AI development and entrepreneurship. Supporting Ghanaian SMEs to build AI solutions for African markets creates jobs while ensuring technology development aligns with local needs and values.

The Choice Before Us

The World Economic Forum predicts AI will destroy 9 million jobs globally over the next five years, but create 19 million new ones. The net positive outcome is not guaranteed, though; it depends on preparation, policy, and proactive adaptation. Ghana has a choice. We can approach AI as a threat to be resisted or as a tool to be mastered. The survey data suggests our people are ready to choose mastery, if our policies support that choice.

The Call to Action

For Policymakers:

- Immediately convene a national AI workforce commission

- Mandate AI literacy in all educational curricula by 2026

- Create tax incentives for businesses investing in worker reskilling

- Establish ethical AI development standards

For Educational Institutions:

- Partner with industry to develop AI-integrated curricula

- Create continuing education programs for working professionals

- Establish AI ethics as a core requirement across all disciplines

For Business Leaders:

- Invest in employee AI training before automation occurs

- Develop human-AI collaboration frameworks

- Create new roles that leverage human oversight of AI systems

For Workers:

- Proactively develop AI-adjacent skills

- Focus on uniquely human capabilities: creativity, ethics, and emotional intelligence

- Seek opportunities to train, govern, and audit AI systems

The Future Starts Now

The respondents in this survey represent Ghana’s future leaders. Their insights reveal both the urgency of our challenge and the strength of our opportunity. AI is not coming to Ghana’s workforce; it is already here. The data shows we have the foundation for success: awareness, engagement, and optimism. What we need now is action. Bold, immediate, and inclusive action that ensures Ghana’s AI future is written by Ghanaians, for Ghanaians. The youth expects educators to incorporate it into learning systems and make AI knowledge and skills part of every student’s learning journey. They want to see leadership enable it by investing in the basic digital and physical infrastructure that makes AI learning possible. Above all, they want leadership and guidance through responsible policy, ethical oversight, and community education. The future of work is not human or machine. It is human and machine, working together to create value we cannot yet imagine. That future starts with the choices we make today.