AI skilling has become Africa’s new promise. From Nairobi to Lagos, Accra to Johannesburg, multinational technology companies are rolling out ambitious programs: free AI tools for students, cloud credits for universities, certification pathways for the workforce. The narrative is compelling, democratizing access to cutting-edge technology, building Africa’s digital future, and closing the skills gap that threatens to leave the continent behind in the AI revolution.

But beneath the glossy presentations and partnership announcements lie questions that are rarely asked publicly, let alone answered with the rigor they demand. As African governments embrace these initiatives and universities sign partnership agreements, we must pause to examine the deeper structural issues being overlooked.

At the Institute for AI Policy & Governance, we believe these questions are not obstacles to AI adoption; they are prerequisites for adoption that actually serve African interests. This article examines four critical dimensions that must anchor any serious conversation about AI skilling in Africa: who pays, who protects, who controls, and what gaps remain.

The “Free” AI Paradox: Who Actually Pays for Access?

When a multinational corporation offers “free” AI access to African students, what does “free” really mean?

The Hidden Infrastructure Tax

Consider a student at a public university in Eastern Africa. She receives access to a cloud-based AI learning platform, no license fee and no subscription cost. The platform is celebrated as democratizing AI education. But to use it, she needs:

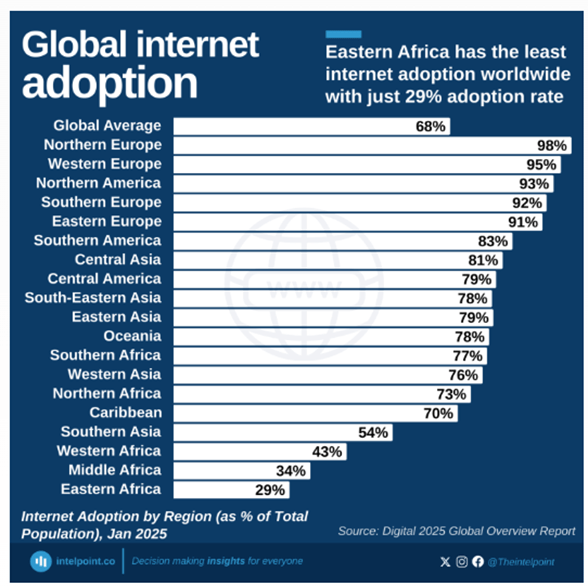

• Reliable internet connectivity: In a region where internet penetration hovers around 29%, this is far from guaranteed

• Consistent data access: At costs ranging from $0.25 to $43.75 per gigabyte across the continent

• A capable device: When laptop ownership at some universities sits at 22.3%

• Stable electricity: To charge devices and maintain connectivity

For this student, “free” AI access requires infrastructure investments that may exceed her family’s monthly income. The platform is free. Access is not.

The Geography of Opportunity

Data from our research reveals stark disparities. Southern Africa, with 73% internet penetration, can genuinely leverage cloud-based AI tools. Central Africa, at 15%, cannot—at least not equitably. Urban students with personal devices and home connectivity thrive. Rural students without either fall further behind.

The result: “Universal” AI access programs systematically advantage already-privileged populations while appearing to serve everyone. We create the appearance of equity while deepening inequality.

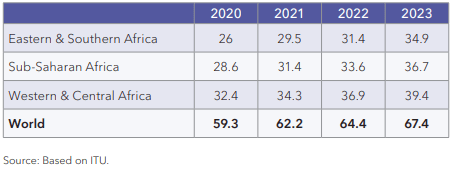

Internet Usage in Africa and the World, 2020-2023

The Long-Term Licensing Question

Many AI skilling programs offer free access during initial periods, often tied to educational partnerships or promotional phases. But what happens when free periods end? What happens when students graduate and need continued access?African institutions, with limited procurement budgets, may find themselves dependent on platforms they cannot afford to lose but lack the power to shape. The infrastructure becomes essential before the business model becomes clear.

Question for policymakers: Are we building sustainable AI capacity, or are we creating dependencies that will require perpetual external subsidy or result in exclusion when commercial terms take effect?

The Data Protection Deficit: Who Protects Student Rights?

As millions of African students engage with AI platforms, they generate extraordinary volumes of data: prompts and queries, learning patterns, creative outputs, behavioral data, and performance metrics. This data is valuable, both educationally and commercially. Yet the systems protecting it are profoundly inadequate.

The Capacity Crisis in Data Protection

African Data Protection Authorities face a sobering reality:

- Budget deficits reaching 76% of needed resources

- Limited technical staff capable of auditing AI systems

- Minimal enforcement mechanisms even when violations are identified

- Jurisdiction challenges when data crosses borders instantly

The result is a regulatory environment that exists on paper but lacks operational capacity. Data protection laws promise student privacy; under-resourced authorities cannot deliver it.

The University Vulnerability

Several African universities might lack:

- Dedicated privacy officers who understand AI data flows

- Dedicated Legal expertise to negotiate complex data processing agreements

- Technical capacity to audit vendor compliance

- Institutional resources to enforce student data rights

When a university signs an agreement with a multinational AI platform, the negotiation is profoundly asymmetric. The vendor knows exactly what data it needs, how it will be processed, where it will be stored, and what secondary uses may occur. The university often does not, and lacks the capacity to find out.

The Consent Fiction

Many AI platforms require students to accept terms of service before access. But can we meaningfully speak of “consent” when:

- Terms are written in complex legal language

- Students have no realistic alternative if they want to participate in their coursework

- Universities have already embedded the platform into required activities

- There is no practical mechanism to opt out without academic penalty

This is not informed consent. It is coerced acceptance of terms students lack the power to refuse or the information to evaluate.

The Cross-Border Data Flow Reality

Student data routinely crosses borders—from African universities to cloud servers in Europe, North America, or Asia. These flows occur with minimal visibility:

- Universities often don’t know where data is stored

- Students aren’t informed about cross-border transfers

- African regulators lack jurisdiction over foreign processing

- There are limited mechanisms to enforce data return or deletion

Question for universities: Do you know where your students’ data is right now? Can you guarantee it is being processed according to the terms you believe you negotiated? Do you have the capacity to audit compliance?

The Sovereignty Question: Who Controls African Students’ Data?

Beyond protection lies another question: control. Even when data is nominally protected, who actually governs how it can be used, retained, analyzed, or monetized?

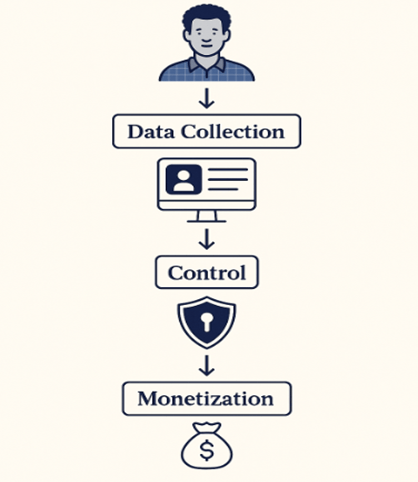

The Value Chain

As African students use AI platforms, their interactions generate value:

• Their prompts help identify edge cases that improve language models

• Their errors reveal where systems need refinement

• Their usage patterns inform product development

• Their creative outputs demonstrate system capabilities

• Their feedback shapes algorithmic improvements

This is not incidental value. This is a core resource that makes AI systems better. Yet the economic benefit of these improvements could accrue entirely outside Africa—to the companies that own the platforms, the shareholders in foreign markets, the economies where these firms are headquartered.

The Model Training Ambiguity

A critical but often obscured question: Are African students’ inputs being used to train AI models?

Many platform terms of service include broad language about “improving our services” or “enhancing user experience.” This language may grant permission to use student data for model training—building the AI systems that generate billions in revenue.

Students and universities rarely understand this implication. And when they discover it, they often lack the power to renegotiate or withdraw.

Question for platforms: State clearly and publicly: Are African students’ prompts, outputs, and interactions being used to train your AI models? If yes, what compensation or benefit returns to those students or their institutions?

The Digital Colonialism Concern

Critics increasingly describe these dynamics as digital colonialism: powerful external actors extracting value from less powerful regions, creating dependencies that constrain future autonomy, and shaping technological trajectories without meaningful input from affected populations.

The comparison resonates because the structural patterns echo:

Question for African governments: Are current AI skilling arrangements building African capacity for self-determined AI futures, or are they creating dependencies that constrain future sovereignty?

The Structural Gaps

Even well-intentioned AI skilling programs often proceed from assumptions that don’t always match African realities. Understanding these gaps is essential to designing interventions that actually work.

Gap 1: The Infrastructure Mirage

AI skilling programs proceed as if infrastructure exists, when it often does not:

- Reliable electricity for charging devices and maintaining connectivity

- Affordable, consistent internet access

- Devices capable of running AI applications

- Technical support when systems fail

- Local data centers reducing latency and cost

Without these foundations, AI skilling becomes a luxury good accessible only to those who already have advantages.

Gap 2: The Institutional Readiness Deficit

Programs assume universities have capacity they frequently lack:

- Procurement expertise to negotiate vendor terms

- Technical staff to evaluate AI tools

- Privacy officers to protect student data

- Risk assessment frameworks for new technologies

- Governance structures for ethical AI deployment

This capacity gap means universities become vulnerable partners, unable to protect their interests or their students’ rights effectively.

Gap 3: The Bias and Performance Problem

AI models trained primarily on Western data show systematic failures in African contexts:

- Speech recognition struggles with African accents and dialects

- Natural language processing misinterprets cultural references

- Image recognition performs poorly on the varied skin tone and features

- Content recommendations lack cultural relevance

- Error rates are systematically higher for African users

When students use tools that don’t work well for them, educational value drops. Frustration rises. The implicit message: these systems weren’t built for you.

Yet skilling programs rarely acknowledge these limitations, let alone address them. Students are left to assume the problem is their own competence rather than systemic bias.

Gap 4: The Labor Market Disconnect

Many AI-skilling programs focus on creating AI-literate graduates without linking to workforce absorption strategies to ensure that corresponding job opportunities exist.

If African economies don’t simultaneously develop AI-using industries, AI-enabled public services, and local AI startups, we risk creating:

- Populations skilled in technologies their economies don’t deploy

- Brain drain as trained workers seek opportunities abroad

- Frustration as education doesn’t translate to employment

- Wasted investment in skills without economic return

Skilling without industrial strategy is incomplete. AI capacity must connect to actual economic transformation.

Gap 5: The Blind Spot

Current strategies inadequately address:

- Gender gaps: A recent ImpactHER survey of over 4,000 women across 52 African countries reveals: Only 49.8% have some form of Internet access, 60% have never received any digital skills training. 86% lack even basic artificial intelligence (AI) proficiency, and 34.7% do not own any digital device.

- Geographic disparities: Programs concentrate in capital cities and major universities

- Language barriers: Training delivered in English or French excludes many

- Disability exclusion: Although accessible interfaces are emerging, they remain uncommon and far from the default.

- Socioeconomic filtering: Programs reach those already advantaged

Without deliberate equity interventions, AI skilling risks becoming another mechanism that advantages the advantaged.

Gap 6: The Governance Vacuum

Perhaps most critically, AI skilling programs deploy with minimal governance oversight:

- No requirement to inventory what AI tools operate in universities

- No mandatory impact assessments before deployment

- No systematic monitoring of outcomes

- No enforcement mechanisms when problems arise

- No clear accountability when systems cause harm

Governments cannot govern what they cannot see. The absence of AI registries, transparency requirements, and accountability mechanisms means deployments happen in a policy blind spot.

What a Governance-First Approach Looks Like

Addressing these questions doesn’t mean rejecting AI skilling. It means doing it properly, with the governance, infrastructure, and equity foundations that make success possible.

Build Before You Scale

Infrastructure First:

- Invest in connectivity, devices, and compute capacity before scaling AI programs

- Ensure equitable access across geographies and socioeconomic groups

- Create sustainable funding models that don’t depend on perpetual external subsidy

Institutional Capacity:

- Resource universities to negotiate as informed partners

- Build data protection expertise within institutions

- Create governance frameworks before deploying at scale

Protect Before You Collect

Student Data Rights:

- Mandate Data Protection Impact Assessments for any educational AI tool

- Require clear disclosure of data flows, storage locations, and usage

- Establish strong consent mechanisms with genuine opt-out options

- Create enforcement mechanisms when violations occur

Cross-Border Controls:

- Regulate data transfers with sovereignty protections

- Require data localization where appropriate

- Ensure African institutions can audit foreign processing

Control Before You Depend

Platform Governance:

- Require transparency about model training using student data

- Negotiate terms that prevent lock-in and preserve alternatives

- Build African-owned AI infrastructure as a strategic priority

- Create vendor accountability mechanisms

Economic Value Capture:

- Ensure benefits from student-generated data return to African institutions

- Link skilling to industrial strategies that create local AI jobs

- Support African AI startups and entrepreneurship

- Build sovereign AI capabilities

Measure What Matters

Equity Indicators:

- Track access by gender, geography, socioeconomic status

- Monitor outcomes, not just participation

- Assess whether programs reduce or widen inequalities

- Publish transparent data on impact

Sovereignty Metrics:

- Document dependencies on external platforms

- Track where value accrues from African AI activity

- Measure progress on African-owned infrastructure

- Assess institutional autonomy over technology decisions

The Path Forward

AI skilling can be transformative for Africa, but only if we ask hard questions before scaling programs that may create more problems than they solve.

The questions in this article are not theoretical. They are immediate, practical, and urgent:

Who pays? If “free” access requires infrastructure most students lack, we’re building inequality into the foundation.

Who protects? If data authorities are under-resourced and universities lack capacity, student rights exist only on paper.

Who controls? If African students’ data trains foreign models that generate foreign profits, we’re repeating extractive patterns.

What gaps remain? If we ignore infrastructure deficits, institutional weaknesses, bias problems, labor market disconnects, equity failures, and governance vacuums, we’re setting up for failure.

A Call for Governance-Led AI Skilling

AIPG calls for AI skilling programs that are:

Infrastructure-Ready: Built on foundations that exist, not assumed

Rights-Protecting: With enforceable data protection and meaningful consent

Sovereignty-Preserving: Ensuring African control over African data and value

Equity-Centered: Deliberately designed to close rather than widen gaps

Governance-First: Transparent, accountable, and subject to oversight

Questions for Stakeholders

For African governments:

- Do you have visibility into what AI systems operate in your universities?

- Have you established data protection requirements for educational AI?

- Are you building sovereign AI infrastructure or deepening dependency?

For universities:

- Can you account for where your students’ data is and how it’s used?

- Do you have the capacity to negotiate as informed partners?

- Have you conducted risk assessments for AI tools you’ve deployed?

For technology companies:

- Will you transparently disclose data flows and model training practices?

- Will you commit to terms that prevent lock-in and preserve alternatives?

- Will you support African infrastructure development, not just platform access?

For students and civil society:

- Are you aware of what happens to data you generate on AI platforms?

- Do you have meaningful voice in decisions about AI deployment?

- Are there mechanisms to report harm and demand accountability?

Conclusion: Sovereignty Through Scrutiny

AI skilling is not simply a technical education challenge. It is a sovereignty question wrapped in an infrastructure challenge wrapped in a governance imperative.

The strategies currently guiding African AI skilling programs are incomplete. They promise access while overlooking who pays for it. They assume protection while ignoring capacity to deliver it. They celebrate partnership while obscuring questions of control. They scale rapidly while leaving critical gaps unaddressed.

This doesn’t make AI skilling unworkable. It makes governance essential.

Africa can build AI-literate populations, vibrant AI industries, and innovative AI applications, but only if we insist on programs that are infrastructure-ready, rights-protecting, sovereignty-preserving, equity-centered, and governance-first.

The questions in this article are uncomfortable. They challenge narratives of frictionless technological progress. They expose asymmetries in power and capacity. They reveal gaps between rhetoric and reality.

But uncomfortable questions are exactly what responsible AI governance requires. And if we want African AI futures shaped by African priorities, we must ask them now, before dependencies deepen, before harms compound, and before the window for meaningful governance closes.

The choice is not whether to pursue AI skilling. The choice is whether to pursue it with eyes open or closed.

AIPG chooses eyes open. We invite African governments, universities, technology companies, civil society, and students to join us in asking the hard questions that make transformative AI skilling possible—on African terms, for African futures.